Puzzle 2008 04 014 Answer

| Author(s) | N.J.W. Verouden, R.J. de Winter, A.A.M. Wilde | |

| NHJ edition: | 2009:01,062 | |

| These Rhythm Puzzles have been published in the Netherlands Heart Journal and are reproduced here under the prevailing creative commons license with permission from the publisher, Bohn Stafleu Van Loghum. | ||

| The ECG can be enlarged twice by clicking on the image and it's first enlargement | ||

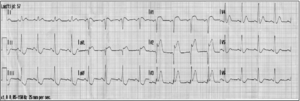

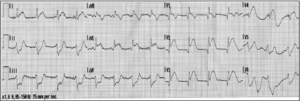

A 57-year-old man collapsed after one hour of angina symptoms in the presence of the alarmed ambulance personnel. He had never had any complaints of chest pain before and his medical history did not contain any cardiac events. Current smoking and a positive family history were noted as risk factors for coronary artery disease. Ventricular fibrillation (VF) was recorded as the first rhythm and the patient was successfully defibrillated with external DC shock. The first ECG after defibrillation is shown in figure 1A, followed by a second ECG (figure 1B) 40 minutes later.

What would be your diagnosis and thoughts?

Answer

The ECG in figure 1A shows sinus rhythm, an intermediate electrical axis, and a normal PQ interval and QRS duration. Furthermore, obvious ST-segment elevation (STE) preceded by pathological Q waves inthe right precordial leads, STE in leads I and aVL, and reciprocal ST-segment depression in the inferior leads all imply an acute occlusion of the left anterior descending (LAD) artery, located proximal to the firstseptal and first diagonal branch.[1][2] The recording in figure 1B reveals a regular rhythm with broadened QRS complexes, likely a ventricular rhythm, of approximately 100 beats/min without visible atrial activation. The broadened QRS complexes(± 0.12 s) show a right bundle branch block (RBBB) configuration and a left anterior fascicular block, which causes the electrical axis to shift leftwards. Corrected QT intervals are normal. ST-segment shifts are com-parable to those in figure 1A. Both the left anterior fascicle and the right bundlebranch are supplied by septal branches of the proximal LAD artery.

Ischaemia-induced bifascicular block, defined as RBBB along with left anterior (or posterior) fascicular block, has been associated with a 30% excess risk of complete heart block and should therefore be regarded as ‘bad news’. Additional prolongation of the PR interval, known as incomplete trifascicular block, is associated with imminent high-degree AV block and temporary or permanent pacing used to be recommended in these circumstances in the days prior to primary PCI.[3][4][5]

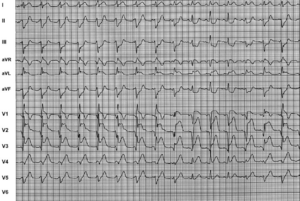

In the pre thrombolytic era, in-hospitalmortality in these patients could be as high as 80%,which was mainly related to an extensive loss of functioning myocardium.[6] In an emergency situation, a brief evaluation of the ECG depicted in figure 1B could lead to the mis-diagnosis of a multifascicular conduction block caused by acute occlusion of the LAD artery. Nevertheless, and in contrary to the ECG in figure 1A, a normal P wave or other forms of atrial pacemaker activity are absent in this recording. Finally, the ECG recorded justprior to emergency coronary angiography (figure 2) shows both electrocardiographic appearances. We see the transition from the regular ventricular rhythm intosinus rhythm with subsequent disappearance of RBBB configuration and left anterior fascicular block.

In conclusion, it is most likely that an intermittent accelerated idioventricular rhythm (AIVR) originating from the left posterior fascicle caused the widened QRS complex rhythm that competes with sinus rhythm. A second, less plausible explanation would be that the atrioventricular node or bundle of His were intermittently acting as the dominant pacemaker, accompanied by ischaemia-induced conduction disturbance of theright bundle branch and left anterior fascicle, which would be an alarming sign of severe ischaemia affecting an extensive part of the myocardium. The emergency coronary angiography revealed an occlusion of the proximal LAD artery, which was successfully treated with primary percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI).

References

- Engelen DJ, Gorgels AP, Cheriex EC, De Muinck ED, Ophuis AJ, Dassen WR, Vainer J, van Ommen VG, and Wellens HJ. Value of the electrocardiogram in localizing the occlusion site in the left anterior descending coronary artery in acute anterior myocardial infarction. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1999 Aug;34(2):389-95. DOI:10.1016/s0735-1097(99)00197-7 |

- Tamura A, Kataoka H, Nagase K, Mikuriya Y, and Nasu M. Clinical significance of inferior ST elevation during acute anterior myocardial infarction. Br Heart J. 1995 Dec;74(6):611-4. DOI:10.1136/hrt.74.6.611 |

- Hindman MC, Wagner GS, JaRo M, Atkins JM, Scheinman MM, DeSanctis RW, Hutter AH Jr, Yeatman L, Rubenfire M, Pujura C, Rubin M, and Morris JJ. The clinical significance of bundle branch block complicating acute myocardial infarction. 2. Indications for temporary and permanent pacemaker insertion. Circulation. 1978 Oct;58(4):689-99. DOI:10.1161/01.cir.58.4.689 |

- Canadian Cardiovascular Society, American Academy of Family Physicians, American College of Cardiology, American Heart Association, Antman EM, Hand M, Armstrong PW, Bates ER, Green LA, Halasyamani LK, Hochman JS, Krumholz HM, Lamas GA, Mullany CJ, Pearle DL, Sloan MA, Smith SC Jr, Anbe DT, Kushner FG, Ornato JP, Pearle DL, Sloan MA, Jacobs AK, Adams CD, Anderson JL, Buller CE, Creager MA, Ettinger SM, Halperin JL, Hunt SA, Lytle BW, Nishimura R, Page RL, Riegel B, Tarkington LG, and Yancy CW. 2007 focused update of the ACC/AHA 2004 guidelines for the management of patients with ST-elevation myocardial infarction: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2008 Jan 15;51(2):210-47. DOI:10.1016/j.jacc.2007.10.001 |

- Gregoratos G, Abrams J, Epstein AE, Freedman RA, Hayes DL, Hlatky MA, Kerber RE, Naccarelli GV, Schoenfeld MH, Silka MJ, Winters SL, Gibbons RJ, Antman EM, Alpert JS, Gregoratos G, Hiratzka LF, Faxon DP, Jacobs AK, Fuster V, Smith SC Jr, and American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines/North American Society for Pacing and Electrophysiology Committee to Update the 1998 Pacemaker Guidelines. ACC/AHA/NASPE 2002 guideline update for implantation of cardiac pacemakers and antiarrhythmia devices: summary article: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines (ACC/AHA/NASPE Committee to Update the 1998 Pacemaker Guidelines). Circulation. 2002 Oct 15;106(16):2145-61. DOI:10.1161/01.cir.0000035996.46455.09 |

- Hindman MC, Wagner GS, JaRo M, Atkins JM, Scheinman MM, DeSanctis RW, Hutter AH Jr, Yeatman L, Rubenfire M, Pujura C, Rubin M, and Morris JJ. The clinical significance of bundle branch block complicating acute myocardial infarction. 1. Clinical characteristics, hospital mortality, and one-year follow-up. Circulation. 1978 Oct;58(4):679-88. DOI:10.1161/01.cir.58.4.679 |