Brugada Syndrome

| Author(s) | P.G. Postema, MD | |

| Moderator | P.G. Postema, MD | |

| Supervisor | ||

| some notes about authorship | ||

The Brugada syndrome is an hereditary disease that is associated with high risk of sudden cardiac death. It is characterized by typical ECG abnormalities: ST segment elevation in the precordial leads (V1 - V3).

Characteristics of the Brugada syndrome:

- Inheritable arrhythmia syndrome with autosomal dominant inheritance. If one of the two parents is affected, each child (both males and females) has a 50% chance of inheriting the disease.

- Males are more often symptomatic than females, probably by the influence of sex hormones on cardiac arrhythmias and/or ion channels, and a different distribution of ion channels across the heart in males versus females.

- The arrhythmias usually occur in patients between 30 and 40 years of age. (range 1-77 yrs) and often during rest or while sleeping (high vagal tone).

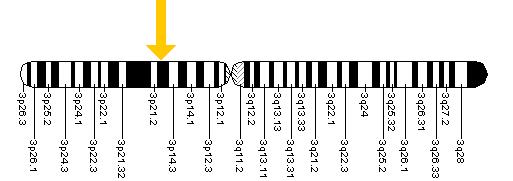

- In only about 30% of patients, genetic defects can be detected in the (SCN5A) gene which encodes the cardiac sodium channel (loss-of-function mutation). In much smaller quantities, mutations may be found in the GPD1L gene (which probably influences cardiac sodium channel function) or in cardiac calcium channel encoding genes (CACNxxx). In the remaining patients, the disease is probably multi-genetic or caused by yet unknown genetic defects.

- The right ventricle is most affected in Brugada syndrome, and particularly (but not specifically) the right ventricular outflow tract .

- The prevalence varies between 5-50:10.000, largely depending on geographic location. In some southeast Asian countries the disease is considered endemic and believed to be the second cause of death among young men (after car accidents). In these countries Brugada syndrome is believed to underly (in part) the 'Sudden Unexpected Death Syndrome' (SUDS). This relation has, however, not been thoroughly investigated and there are almost no epidemiological studies into Brugada syndrome ECGs (apart from Japan). In different Asian countries, different names have been given to SUDS: in the Phillipines it is called bangungut (to rise and moan in sleep) and in Thailand lai tai (death during sleep).

The Brugada brothers were the first to describe the characteristic ECG findings and link them to sudden death. Before that, the characteristic ECG findings, were often mistaken for a right ventricle myocardial infarction and already in 1953, a publication mentions that the ECG findings were not associated with ischemia as people often expected.osher

Diagnosis and treatment

- Patients who are symptomatic (unexplained syncopes, ventricular tachycardias or aborted sudden cardiac death) may have a symptom recurrence risk of 2 to 10% per year. In these patients an ICD implant is advisable. Further, life-style advice is given (see below).

- Some groups advise an electrophysiological investigation (inducibility of ventricular fibrillation) for risk assessment in Brugada patients,brug2brug3 but others could not reproduce the predictive value of these tests,priorieckhardt so the value of inducibility is controversial.

- In large studies familial sudden death did not appear to be a risk factor for sudden death in siblings.

- In asymptomatic patients in whom the Brugada ECG characteristics are present (either spontaneously or provoked by fever or sodium channel blockers like ajmaline, procainimde or flecainide) life style advice is given. This advice includes:

- A number of medications should not be taken (including sodium channel blockers and certain anti-depressants and anti-arrhythmics, see www.BrugadaDrugs.org)

- Rigorous treatment of fever with paracetamol/Tylenol, as fever may elicit a Brugada ECG and arrhythmias in some patients.

- Spontaneous Type I ECGs do appear to be more prevalent in patients who experienced symptoms.

For a full list of the diagnostic criteria, see Wilde

Electrocardiographic criteria

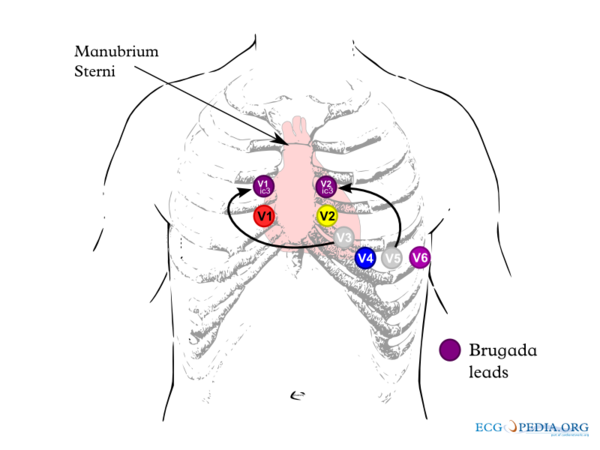

Three ECG repolarization patterns in the right precordial leads are recognized in the diagnosis of Brugada syndrome.

Type I is the only ECG criterion that is diagnostic of Brugada syndrome. The type I ECG is characterized by a J elevation >=2 mm (0.2 mV) a coved type ST segment followed by a negative T wave (see figure). Brugada syndrome is definitively diagnosed when a type 1 ST-segment is observed in >1 right precordial lead (V1 to V3) in the presence or absence of a sodium channel–blocking agent, and in conjunction with one of the following:

- documented ventricular fibrillation (VF)

- polymorphic ventricular tachycardia (VT)

- a family history of sudden cardiac death at <45 years old

- coved-type ECGs in family members

- inducibility of VT with programmed electrical stimulation

- syncope

- nocturnal agonal respiration.

The sensitivity of the ECG for Brugada syndrome can be increased with placement of ECG leads in the intercostal space above V1 and V2 (V1ic3 and V2ic3)

Electrocardiograms of Brugada patients can change over time from type I to type II and/or normal ECGs and back. A type III ECG is rather common and is considered a normal variant, but also the Type II is a normal variant (albeit suggestive of Brugada syndrome).

A recent study suggests that fractionation of the QRS complex is a marker of a worse prognosis in Brugada syndrome.Morita

| Type I | Type II | Type III | |

|---|---|---|---|

| J wave amplitude | >= 2mm | >= 2mm | >= 2mm |

| T wave | Negative | Positive or biphasis | Positive |

| ST-T configuration | Coved type | Saddleback | Saddleback |

| ST segment (terminal portion) | Gradually descending | Elevated >= 1mm | Elevated < 1mm |

- Examples of Brugada syndrome type I

-

Brugada ECG during ajmaline testing

- Examples of Brugada syndrome type II

External links

- Cardiogenetics website of the AMC cardiogentica.nl

- Brugada.org

- Genereview Brugada

- Brugada drugs contains lists of medications that should be avoided in patients with Brugada syndrome and medication that can be used to diagnose the syndrome

Referenties

<biblio>

- Wilde pmid=15898165

- Brugada pmid=1309182

- osher pmid=13104407

- brug2 pmid=11772879

- brug3 pmid=12776858

- priori pmid=11901046

- Wilde2 pmid=12417552

- Morita pmid=18838563

- eckhardt pmid=15642769

</biblio>