A Concise History of the ECG: Difference between revisions

mNo edit summary |

mNo edit summary |

||

| Line 5: | Line 5: | ||

==1600-1800== | ==1600-1800== | ||

'''1600.''' William Gilbert, Physician to Queen Elizabeth I, President of the Royal College of Physicians, and creator of the 'magnetic philosophy' introduces the term 'electrica' for objects (insulators) that hold static electricity. He derived the word from the Greek for amber (electra). It was known from ancient times that amber when rubbed could lift light materials. Gilbert added other examples such as sulphur and was describing what would later be known as 'static electricity' to distinguish it from the more noble magnetic force which he saw as part of a philosophy to destroy forever the prevailing Aristotlean view of matter. <cite>Gilbert</cite> | '''1600.''' William Gilbert, Physician to Queen Elizabeth I, President of the Royal College of Physicians, and creator of the 'magnetic philosophy' introduces the term 'electrica' for objects (insulators) that hold static electricity. He derived the word from the Greek for amber (electra). It was known from ancient times that amber when rubbed could lift light materials. Gilbert added other examples such as sulphur and was describing what would later be known as 'static electricity' to distinguish it from the more noble magnetic force which he saw as part of a philosophy to destroy forever the prevailing Aristotlean view of matter. <cite>Gilbert</cite> | ||

1649. Sir Thomas Browne, Physician, whilst writing to dispel popular ignorance in many matters, is the first to use the word 'electricity'. Browne calls the attractive force "Electricity, that is, a power to attract strawes or light bodies, and convert the needle freely placed". (He is also the first to use the word 'computer' - referring to people who compute calendars.)<cite>Browne</cite> | |||

'''1649.''' Sir Thomas Browne, Physician, whilst writing to dispel popular ignorance in many matters, is the first to use the word 'electricity'. Browne calls the attractive force "Electricity, that is, a power to attract strawes or light bodies, and convert the needle freely placed". (He is also the first to use the word 'computer' - referring to people who compute calendars.)<cite>Browne</cite> | |||

'''1660'''. Otto Von Guericke builds the first static electricity generator. | |||

==1850-1900== | ==1850-1900== | ||

Revision as of 15:41, 12 May 2008

The history of the ECG goes back more than one and a half century

1600-1800

1600. William Gilbert, Physician to Queen Elizabeth I, President of the Royal College of Physicians, and creator of the 'magnetic philosophy' introduces the term 'electrica' for objects (insulators) that hold static electricity. He derived the word from the Greek for amber (electra). It was known from ancient times that amber when rubbed could lift light materials. Gilbert added other examples such as sulphur and was describing what would later be known as 'static electricity' to distinguish it from the more noble magnetic force which he saw as part of a philosophy to destroy forever the prevailing Aristotlean view of matter. Gilbert

1649. Sir Thomas Browne, Physician, whilst writing to dispel popular ignorance in many matters, is the first to use the word 'electricity'. Browne calls the attractive force "Electricity, that is, a power to attract strawes or light bodies, and convert the needle freely placed". (He is also the first to use the word 'computer' - referring to people who compute calendars.)Browne

1660. Otto Von Guericke builds the first static electricity generator.

1850-1900

In 1843 Emil Du Bois-Reymond, a german physiologist, was the first to describe "action potentials" of muscular contraction. He used a highly sensitive galvanometer, which contained more than 5 km of wire. Du Bios Reymond named the different waves: "o" was the stable equilibrium and he was the first to use the p, q, r and s to describe the different waves. Dubois However, in his excellent paper on the 'Naming of the waves in the ECG' Dr Hurst credits Einthoven for being the first to use PQRS and T.Hurst

In 1850 M. Hoffa described how he could induce irregular contractions of the ventricles of doghearts by administering electrical shock. Hoffa

In 1885 Chauveau was the first to describe complete heart block in a horse while observing ventricular beats without movement of the atrial auricles.

In 1887 the English physiologist Augustus D. Waller from Londen published the first human electrocardiogram. He used a capillar-electrometer. WallerWaller2

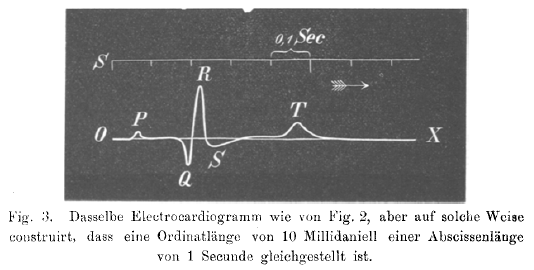

The dutchman Willem Einthoven (1860-1927) introduced in 1893 the term 'electrocardiogram'. He described in 1895 how he used a galvanometer to visualize the electrical activity of the heart. In 1924 he received the Nobelprize for his work on the ECG. He connected electrodes to a patienta showed the electrical difference between two electrodes on the galvanometer. We still now use the term: Einthovens'leads. The string galvanometer (see Image) was the first clinical instrument on the recording of an ECG.

1900-1950

In 1905 Einthoven recorded the first 'telecardiogram' from the hospital to his laboratoy 1.5 km away.

In 1906 Einthoven published the first article in which he described a series of abnormal ECGs: left- and right bundlebranchblock, left- and right atrialdilatation, the U wave, notching of the QRS complex, ventricular extrasystoles, bigemini, atrialflutter and total AV block. Einthoven

1950-2000

2000-

External Links

- ECG history on ECGlibrary.com

- History of electrophysiology on the website of the Heart Rhythm Society

References

<biblio>

- Dubois Du Bois-Reymond, E. Untersuchungen über thierische Elektricität. Reimer, Berlin: 1848.

- Waller2 Waller AD. Introductory Address on The Electromotive Properties of the Human Heart. Brit. Med J, 1888;2:751-754

- Chauveau Chauveau MA. De La Dissociation Du Rythme Auriculaire et du Rythme Ventriculaire. Rev. de Méd. Tome V. - Mars 1885: 161-173.

- Hoffa Hoffa M, Ludwig C. 1850. Einige neue versuche uber herzbewegung. Zeitschrift Rationelle Medizin, 9: 107-144

- Waller Waller AD. A demonstration on man of electromotive changes accompanying the heart's beat. J Physiol (London) 1887;8:229-234

- Einthoven Einthoven W. Le telecardiogramme. Arch Int de Physiol 1906;4:132-164

- Einthoven2 Einthoven W. Über die Form des menschlichen Electrocardiogramms. Pfügers Archiv maart 1895, pagina 101-123

- Marey Marey EJ. Des variations electriques des muscles et du couer en particulier etudies au moyen de l'electrometre de M Lippman. Compres Rendus Hebdomadaires des Seances de l'Acadamie des sciences 1876;82:975-977

- Marquez pmid=12177632

- Hurst pmid=9799216

- Gilbert Gilbert W. De Magnete, magneticisique corporibus, et de magno magnete tellure. 1600

- Browne Browne, Sir Thomas. Pseudodoxia Epidemica: Or, enquiries Into Very Many Received Tenents, and Commonly Presumed Truths. 1646: Bk II, Ch. 1. London

</biblio> </references>