Brugada Syndrome

| Author(s) | P.G. Postema, MD | |

| Moderator | P.G. Postema, MD | |

| Supervisor | ||

| some notes about authorship | ||

The Brugada syndrome is an hereditary disease that is associated with higher risk of sudden cardiac death. It is characterized by typical ECG abnormalities: ST segment elevation in the precordial leads (V1 - V3).

Characteristics of the Brugada syndrome:

- autosomal dominant inheritance. If one of both parents are affected, their children have a 50% chance of inheriting the disease.

- Man are more often symptomatic than women, probably by the influence of sex hormones on cardiac arrhythmias.

- The arrhythmias usually occur between 30 and 40 years of age. (range 1-77 yrs) and often during rest or while sleeping.

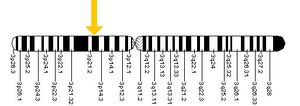

- Only in about 30% of patients, genetic defects can be detected in the (SCN5A) gen. In the other patients the disease is probably multi-genetic or caused by yet unknown genetic defects.

- The right ventricular outflow tract (right before the pulmonary valve) is most affected in the Brugada syndrome.

- The prevalence varies between 5-50:10.000, largely depending on geographic location. In some south-east Asian countries the disease is endemic and sometimes considered the second cause of death amongst young men (after car accidents). There it is called 'Sudden Unexpected Death Syndrome' (SUDS). In different Asian countries, different names have been given to the syndrome: in the Phillipines it is called bangungut (to rise and moan in sleep) and in Thailand lai tai (death during sleep)

The Brugada brothers were the first to describe the characteristic ECG findings and link them to sudden death. Before that, the characteristic ECG findings, were often mistaken for a right ventricle myocardial infarction and already in 1953, a publication mentions that the ECG findings were not associated with ischemia as people often expected.[2]

Diagnosis and treatment

- Patients who are symptomatic (syncope, ventricular tachycardias or survivors of sudden cardiac death) have a mortality risk of up to 10% per year. In these patients an ICD should be implanted.

- Some groups advice an electrofysiologic investigation for risk assessment in Brugada patients,[3][4] but others could not reproduce the predicive value of these tests,[5][6] so this is still controversial.

- In large studies familiar sudden death is not a risk factor for sudden death in siblings.

- In asymptomatic patients in whom the Brugada ECG characteristics are present either spontaneously or provoked by fever or sodium channel blockers (ajmaline, flecainide) life style advices are given, which include:

- A number of medications should not be taken (amongst others beta-blockers, and sodium channel blockers such as certain anti-depressants and anti-arrhythmics)

- Rigorous treatment of fever with paracetamol / Tylenol

For a full list of the diagnostic criteria, see [7]

Electrocardiographic criteria

Three ECG repolarization patterns in the right precordial leads are recognized in the diagnosis of Brugada syndrome.

Type I is the only ECG criterium that is diagnostic of Brugada syndrome. Type I repolarization is characterized by a coved ST-segment elevation >=2 mm (0.2 mV) followed by a negative T wave (see figure). Brugada syndrome is definitively diagnosed when a type 1 ST-segment elevation is observed in >1 right precordial lead (V1 to V3) in the presence or absence of a sodium channel–blocking agent, and in conjunction with one of the following:

- documented ventricular fibrillation (VF)

- polymorphic ventricular tachycardia (VT)

- a family history of sudden cardiac death at <45 years old

- coved-type ECGs in family members

- inducibility of VT with programmed electrical stimulation

- syncope

- nocturnal agonal respiration.

Electrocardiograms of Brugada patients can change over time from type I to type II ECGs and back. A type III ECG is rather common and is concidered a normal variant.

| Type I | Type II | Type III | |

|---|---|---|---|

| J wave amplitude | >= 2mm | >= 2mm | >= 2mm |

| T wave | negative | positive or biphasis | positive |

| ST-T configuration | coved type | saddleback | saddleback |

| ST segment (terminal portion) | gradually descending | elevated >= 1mm | elevated < 1mm |

- Examples of Brugada syndrome type I

- Examples of Brugada syndrome type II

External links

- Cardiogenetics website of the AMC cardiogentica.nl

- Brugada.org

- Genereview Brugada

Referenties

- Brugada P and Brugada J. Right bundle branch block, persistent ST segment elevation and sudden cardiac death: a distinct clinical and electrocardiographic syndrome. A multicenter report. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1992 Nov 15;20(6):1391-6. DOI:10.1016/0735-1097(92)90253-j |

- OSHER HL and WOLFF L. Electrocardiographic pattern simulating acute myocardial injury. Am J Med Sci. 1953 Nov;226(5):541-5.

- Brugada J, Brugada R, Antzelevitch C, Towbin J, Nademanee K, and Brugada P. Long-term follow-up of individuals with the electrocardiographic pattern of right bundle-branch block and ST-segment elevation in precordial leads V1 to V3. Circulation. 2002 Jan 1;105(1):73-8. DOI:10.1161/hc0102.101354 |

- Brugada P, Brugada R, Mont L, Rivero M, Geelen P, and Brugada J. Natural history of Brugada syndrome: the prognostic value of programmed electrical stimulation of the heart. J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol. 2003 May;14(5):455-7. DOI:10.1046/j.1540-8167.2003.02517.x |

- Priori SG, Napolitano C, Gasparini M, Pappone C, Della Bella P, Giordano U, Bloise R, Giustetto C, De Nardis R, Grillo M, Ronchetti E, Faggiano G, and Nastoli J. Natural history of Brugada syndrome: insights for risk stratification and management. Circulation. 2002 Mar 19;105(11):1342-7. DOI:10.1161/hc1102.105288 |

- Eckardt L, Probst V, Smits JP, Bahr ES, Wolpert C, Schimpf R, Wichter T, Boisseau P, Heinecke A, Breithardt G, Borggrefe M, LeMarec H, Böcker D, and Wilde AA. Long-term prognosis of individuals with right precordial ST-segment-elevation Brugada syndrome. Circulation. 2005 Jan 25;111(3):257-63. DOI:10.1161/01.CIR.0000153267.21278.8D |

- Antzelevitch C, Brugada P, Borggrefe M, Brugada J, Brugada R, Corrado D, Gussak I, LeMarec H, Nademanee K, Perez Riera AR, Shimizu W, Schulze-Bahr E, Tan H, and Wilde A. Brugada syndrome: report of the second consensus conference. Heart Rhythm. 2005 Apr;2(4):429-40. DOI:10.1016/j.hrthm.2005.01.005 |

- Wilde AA, Antzelevitch C, Borggrefe M, Brugada J, Brugada R, Brugada P, Corrado D, Hauer RN, Kass RS, Nademanee K, Priori SG, Towbin JA, and Study Group on the Molecular Basis of Arrhythmias of the European Society of Cardiology. Proposed diagnostic criteria for the Brugada syndrome: consensus report. Circulation. 2002 Nov 5;106(19):2514-9. DOI:10.1161/01.cir.0000034169.45752.4a |